Harry Morey Callahan: Kansas City (1981)

Harry Morey Callahan (1912–99) was an American photographer who showed us glimpses of the ordinary and everyday. His graphically strong photographs possess a strangeness: subjects – whether objects or people – seem out of context and enigmatic yet simultaneously grounded by an earthy reality. Callahan’s influence on contemporary photography cannot be understated.

Widely known for his black-and-white images, Callahan was also one of the first photographers, like his contemporary William Eggleston, to experiment with colour film, and, after retiring from teaching photography in the 1970s, he focused primarily on colour work. It is these latter images that interest me: although they retain his trademark hyper-reality, colour is now integral.

Callahan went out almost every day with his camera, taking numerous photographs of his city. Although some consider his photographs mundane, thought and care went into their selection: he produced no more than half a dozen final images each year.

Kansas City (1981)

▲ © The Estate of Harry Callahan

I’ve admired Callahan’s work ever since I encountered Kansas City, which remains one of my favourite photographs.

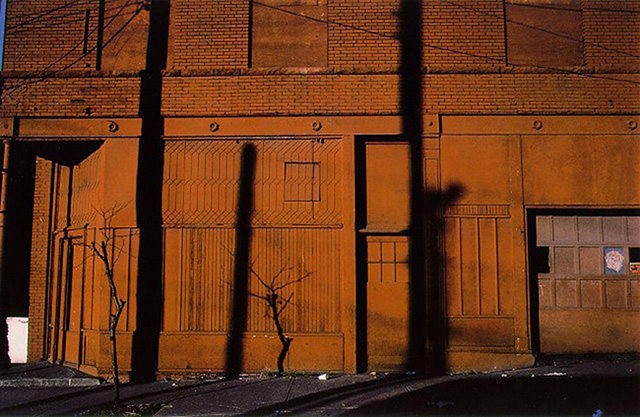

So, what were my thoughts when I first saw Kansas City? I was struck immediately by inactivity and warmth: the industrial outskirts of a city on a torpid afternoon. The quality of the light and the sliver of deep blue sky mitigate against winter; the leafless tree suggests spring – but perhaps it’s summer and the tree is dead. After that initial impression, the oppressive shadows and lack of people and movement became increasingly palpable. Questions arose: Why is everything painted? What is the building for? Where is everyone?

In Kansas City, the ordinary is made extraordinary. Confronted with a face-on view of a building, we try and make sense of it; a difficult task, as everything is painted a dull red – the walls, the doors, even the window panes – and our eye wanders around the frame, overwhelmed by this solid mass of colour. However, features soon resolve: the harsh shadows of the telegraph poles and the tree, the door to the right with the three odd panes, the dark opening to the left with the white box-like object, and a small white cup in the centre.

These details in their stark isolation appear full of meaning – unknowable portents that conjure up Heidegger’s dasein, but with a twist: dasein is about being in the present, but Callahan shows us a past we never encountered, so – unable to engage with the here and now – memories surface instead and gain significance.

And everything revolves around that small white cup: it’s just a carelessly discarded cup, yet why does it seem so important? But that may just be me: Barthes’ punctum.